Across nearly a century, “Abu” Mazharuddin Ahmed (1934-2023) was a surgeon, a father, a grandfather, and a loving husband. He and I spent countless hours together, Star Plus gracing the turmeric-spiced air with tepid arguments in Hindi and furious looks. Abu and his wife Kumudini, which means lily, were married for more than 60 years alone, surviving the precipitous fall of the British Empire. My grandfather and his wife were lucky to escape during the Partition of India and East Bengal in 1947, the former taking refuge from the fighting amidst the Armenian community in Dhaka. Other family came later, during the 1971 War of Independence, which despite its obscurity to the Western mind, claimed more lives than American war in Vietnam. The path of his descendants has been transformed hugely by his decision to leave Bengal, and my multiracial existence made possible by it.

Abu was a shy boy, the fourth brother in a sprawling family. In his youth he aspired to be a cricketer, growing up between Calcutta – the regional capital at the time – and a whole host of other places. He would continue this trend of cosmopolitanism well into his working years. His father, nicknamed “The Tiger”, was a fearsome man who won the title of Khan Bahadur, equivalent to a CBE today. His first three brothers were too obstinate to become medical men, but Abu was forthcoming, embarking on a successful career as an otorhinolaryngological specialist. His eldest brother became a central banker, inventing the currency of Bangladesh (the Taka) in 1972. Because the family was so large, it was impossible to always be the best. Moreover, given the age differences, the Ahmed siblings practically raised one another, as they did on my grandmother’s side too. He remembered fondly riding to the cinema with a younger sibling on his handlebars – and the flashy European car that his father drove, in a time when Bangladesh was still mostly rivers and jungles.

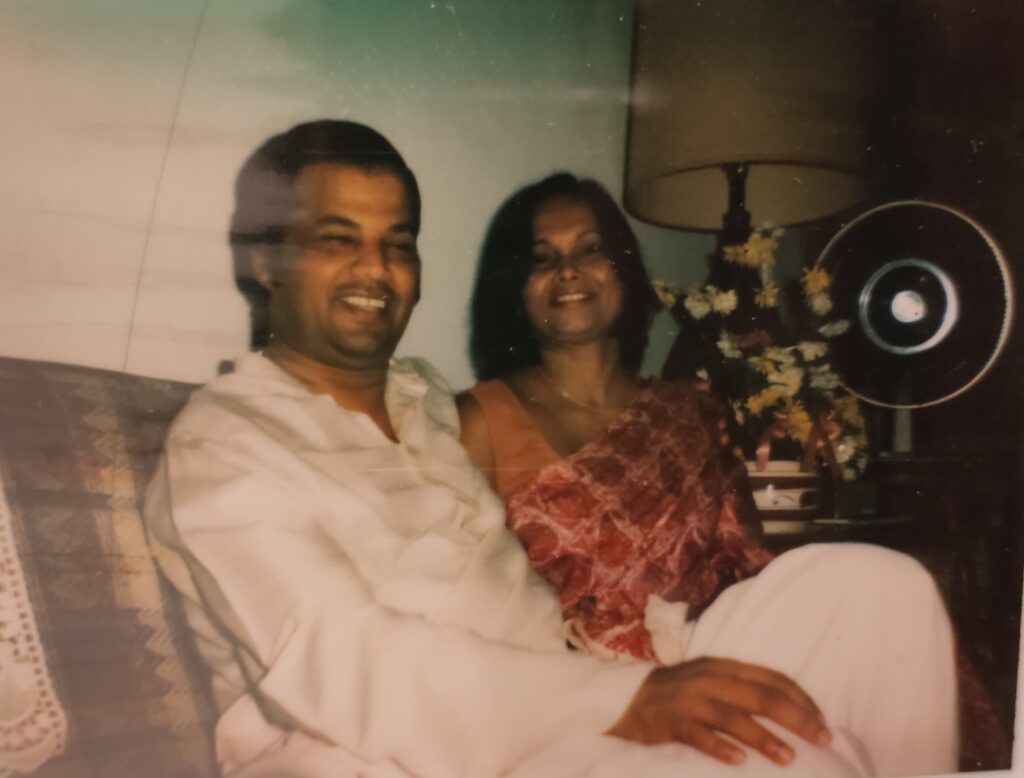

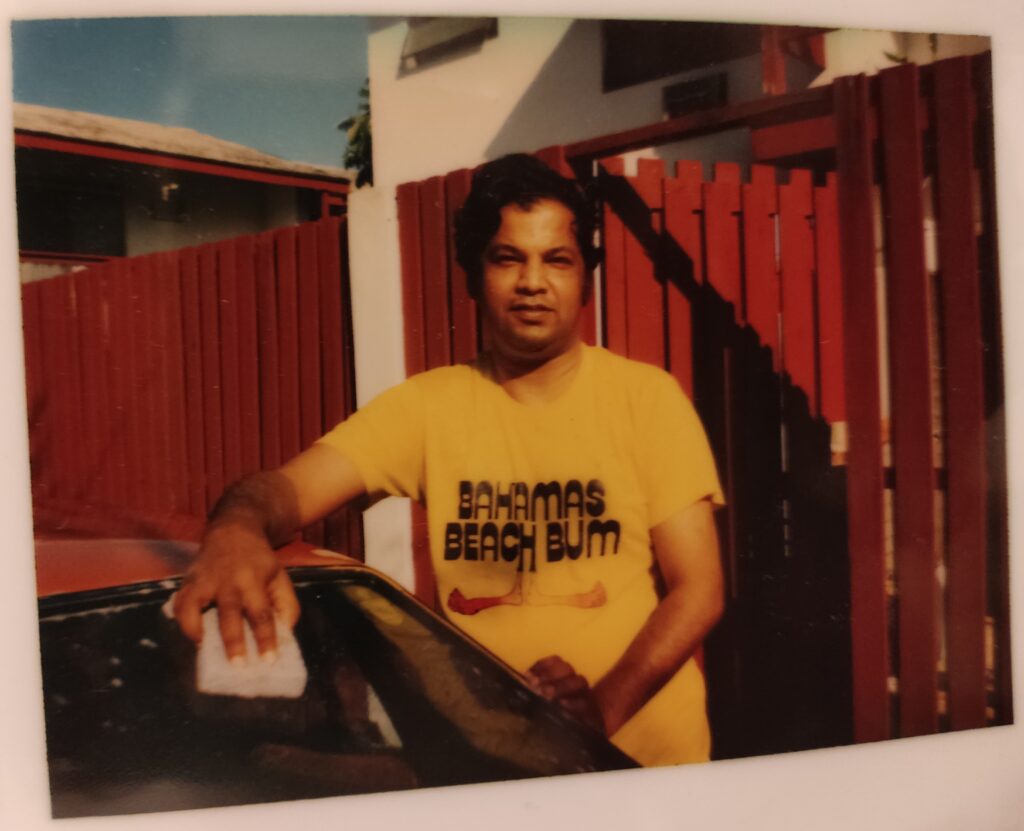

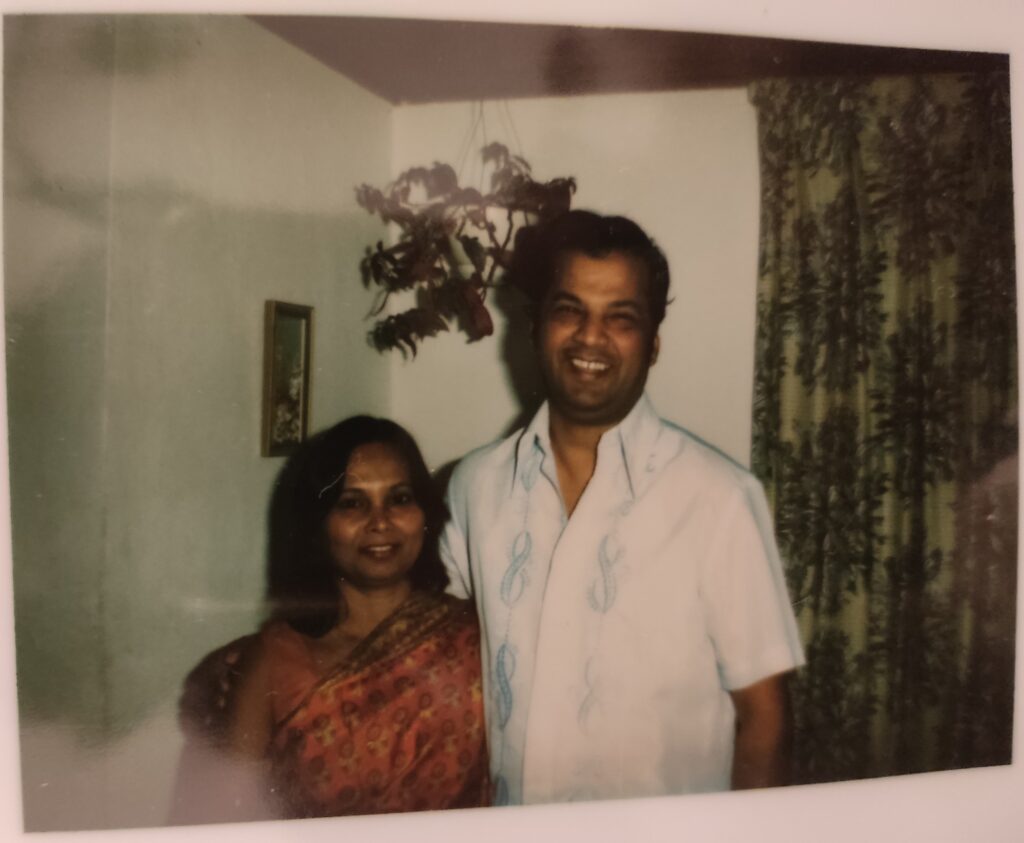

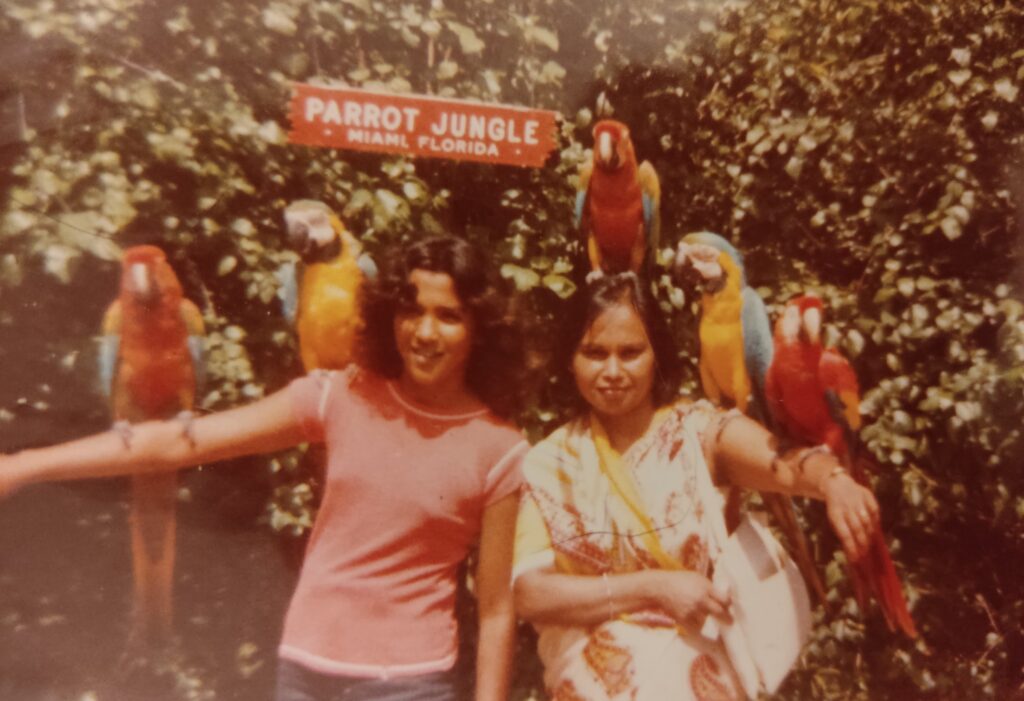

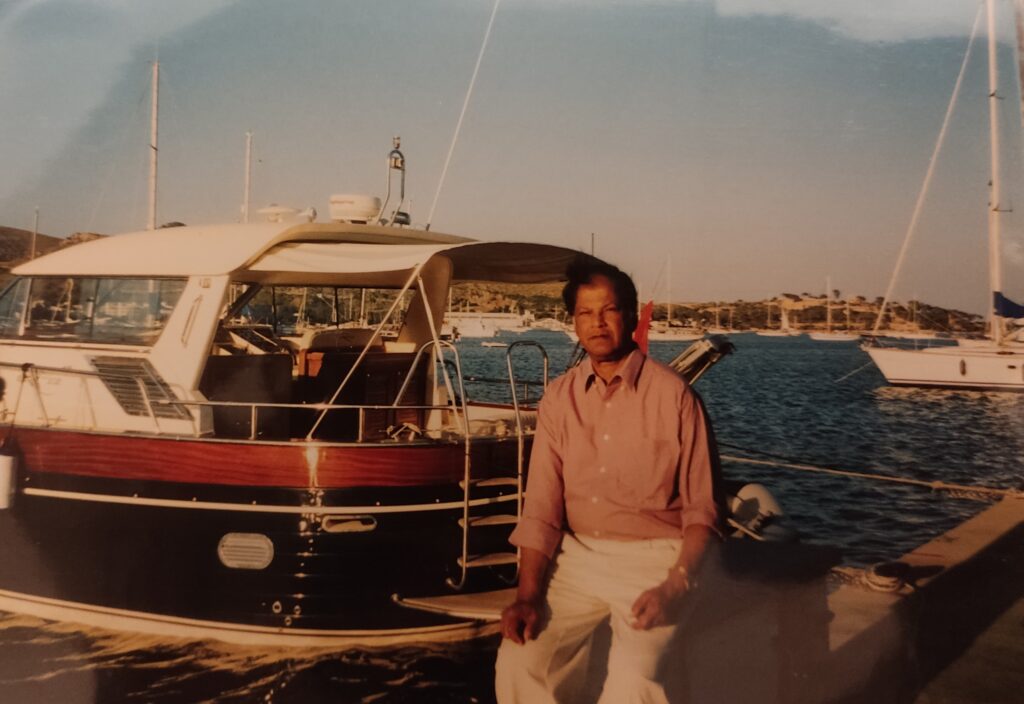

Abu tried relentlessly to pass the Fellowship exam for the Royal College of Surgeons and worked hard as a young doctor to establish himself in Ear, Nose and Throat consultancy. The young family moved frequently to new places in search of jobs; my mother switched schools almost every year. The highlight of their family life came with a move to The Bahamas. Abu was the very first, and therefore, the only ENT consultant in the entire country. Thus, when influential figures got a fish bone stuck in their throat or a nasty ear infection whilst in the Caribbean, Abu was their port of call. Settling for several years there, my mother used to swim for hours every day, and stepping between shadows, traversed the whole island barefoot. Her feet would go black, but she didn’t care. Meanwhile, my grandma was enjoying the high life of expat and retired society, bouncing from dinner party to dinner party. Lobster, caviar, champagne – Kumu was a society woman, able and willing to talk to anyone, no matter their age, creed, or colour. In fact, despite the intensity of his middle years, Abu was often the one doing the housework! He continued his little traditions of shopping for himself and meticulously tidying the house well into old age, even learning to cook at the age of 80 whilst his wife made her final visit to Bangladesh. He made a mean duck à l’orange.

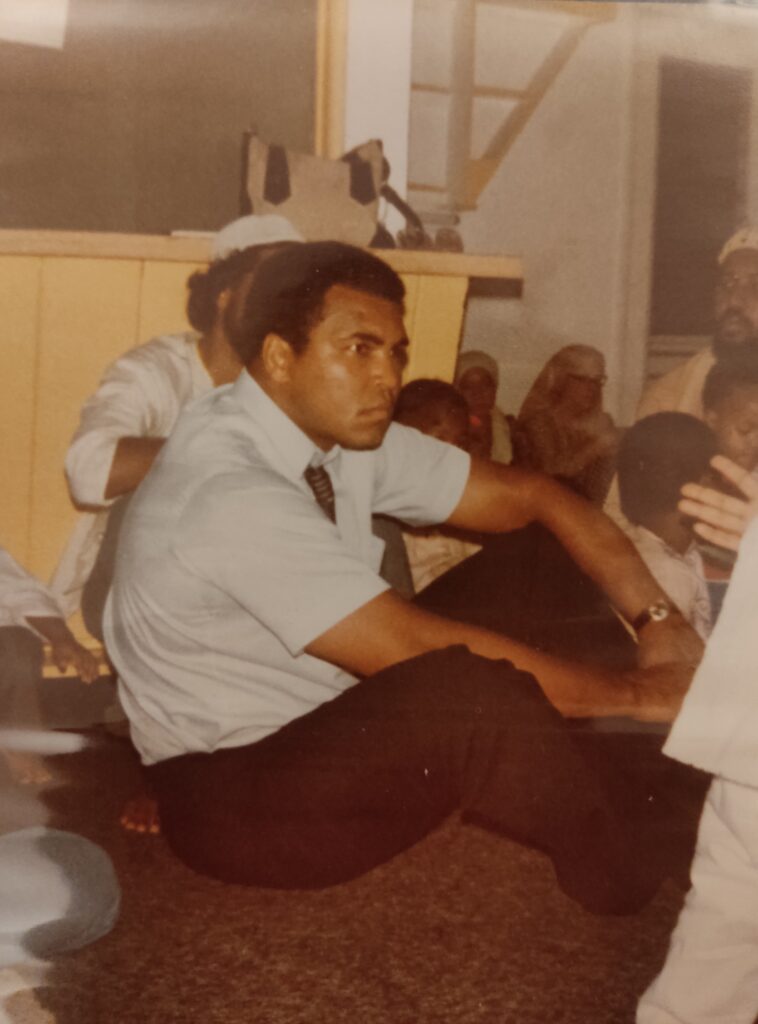

Abu was a humble man, and it was only until recently, when he no doubt became aware of his mortality, that I started learning about his backstory. He prayed with Muhammad Ali, having treated him for being repeatedly punched in the throat. It turns out that at the time Ali was preparing for 1974’s Rumble in the Jungle fight with George Foreman, which was called the greatest sporting event of the 20th century. I had no idea about this until after he died, and the scrapbooks of old photos began to be broken out. Nor did I know that he spoke 5 languages – English, Bengali, Hindi, Arabic, and Urdu. I couldn’t believe that the family had gone diving with Jacques Cousteau, in the original metal suits, despite the fact that they couldn’t exactly swim. Although Abu was a very switched-on man, a mental acuity that continued right up to the final days before his death, our time together was often silent.

Instead, our mouths and tongues were occupied by snacks. Snacks, snacks, so many snacks. I can still remember the exact inflection of Kumu’s voice when she asked me “Do you want a snack?”, with the Bengali S, and that knowing raised pitch at the end. Samosas were the favourite for a long time, but Jaffa Cakes were too; so tantalising that my grandparents had to spell each letter out individually when mentioning them to avoid whipping me into a feeding frenzy. South Asians will be more than familiar with the delights that a hot jalebi, a warm dahl puri, chana chur with muri, or a Bengali-style bhaji hold. I’m still trying to replicate Kumu’s pakora recipe.

Later in life, Abu and Kumu moved to Saudi. The list of other potential options – Libya and Syria – speaks to just how different the world was then. The latter two were considered amiable destinations for a private practice doctor, being as moderate and relaxed as my grandfather was. In 1980s Saudi, however, there were no cinemas, abayas were compulsory, and men and women hardly intermixed. In fact, women didn’t really leave the house at all, confined to a domesticity that my grandma had ironically never experienced before. It was a huge lifestyle change for Kumu, who is still the most extroverted person I have ever met. Her only daughter had flown the nest. So, after saving up their pennies, the couple returned to England.

In anticipation of a third phase of life, they moved close to my mother when I was conceived to share the burden of child care as much as possible. Their house was my second home, and sometimes, even my first home. My parents took a trip to Venice for their tenth wedding anniversary, in light of which I was deposited at Abu’s house, along with my brother. I was so bewildered at the possibility of seeing my grandparents not just after school, but before school in the morning too, that I cried. However, I soon acquiesced, bribed daily by potato waffles and set honey.

By virtue of some of these thoughts, I hope Abu will be remembered by the generations to come, his stories told and retold. On Saturday, the world lost a remarkable man, who in perfect honesty, lived through more than most of us can ever expect to live through, more than most of us can ever expect to achieve. Rest in Peace, দাদা.

Wow! So beautifully told. What an amazing life of of your grand father.

I was lucky enough to spend some time with them, in London, 1983. The story you narrate totally jars with my experience, son of a tiger.

Thank you for writing. God bless you and you family.

It’s beautifully written and a wonderful tribute. Sorry for your loss, your grandfather seemed to have lived a fascinating life. May he rest in peace.